I just read a couple more books — one through BookRiot’s marvelous Daily Deals aggregator, one (finally!) that I bought from a used bookstore on my trip this summer.

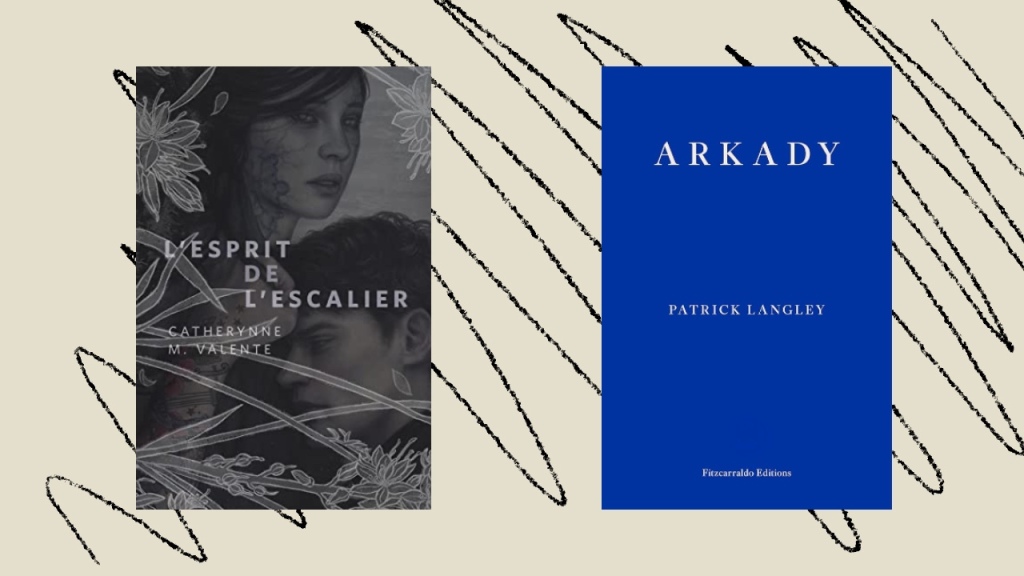

L’Esprit de L’Escalier by Catherynne M. Valente (Tor.com) follows the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice — Eurydice, who’s suffered an untimely death, and Orpheus, her failed hero who, in the original story, is unable to successfully draw her back up from Hades. In Valente’s retelling, Eurydice has returned to the surface of the earth. Orpheus did it — he refused to turn around to check on his wife, allowing Eurydice to follow him back to the land of the living. But is this really a good thing, or did he just assume she’d follow him everywhere forever and ever? In this new version of marriage, she may be on the surface of the earth, but she’s still dead, Orpheus a superstar musician who’s endlessly burdened by her new particularities. Mold grows from the ceilings, walls, her skin, dampness and fug abound, food is useless to her, and her body is constantly falling apart… The pace of the book too is damp, plodding, but I really liked it anyhow. This was an interesting, creative contemporary take on an already complex myth. Ultimately it was more of a “scene” than a book. Felt like a really detailed diorama.

Arkady is a novel by Patrick Langley (Fitzcarraldo), and is mostly set in the UK, where two brothers are trying to come up in a struggling working-class post-industrial world. The first chapter explains their childhood as they’re unmoored from both parents and begin to find their own way. Then the narrative flips to their early adulthood in a major, crumbling city. They live with an older, dying caretaker, and then squat with each other in various warehouses, empty buildings, a boat, a failed utopia, and finally a sinking town, as capitalism wheezes its last dying breaths around them. I had trouble with the timelines of this book — the story jumped ahead, and then back, to explain itself. The boys hunted for the Red Citadel, a temporary anarchist utopia, and then were just as quickly forced on. Langley talked through what characters were thinking, often in moments when the narrative could’ve benefited from more plot development instead. But this book’s strength lies fully in the landscape. I love the way Langley describes the fight between the natural world and industry. A reader could easily flip to any page to see what I mean. Example:

Pigeons thronged the distant eves, foxes padded through blast furnaces and rolling mills, mice scuttled down huge ceramic vats and spindly conveyor belts.

Trees grew slantwise in the mortar.

In one of the rooms, where a huge furnace stood like an oversized human heart, bulging with veins of chrome, a hole in the roof allowed sunlight to pierce the gloom, and in this pool of light a twisted, hard-leafed shrub had grown.

Ultimately the only “city” necessary for the two boys is, well, each other. I am not sure this book does anything incredibly original, but I was drawn to the air of environmental/anti-capitalist protest, which really reminded me of the Occupy era.